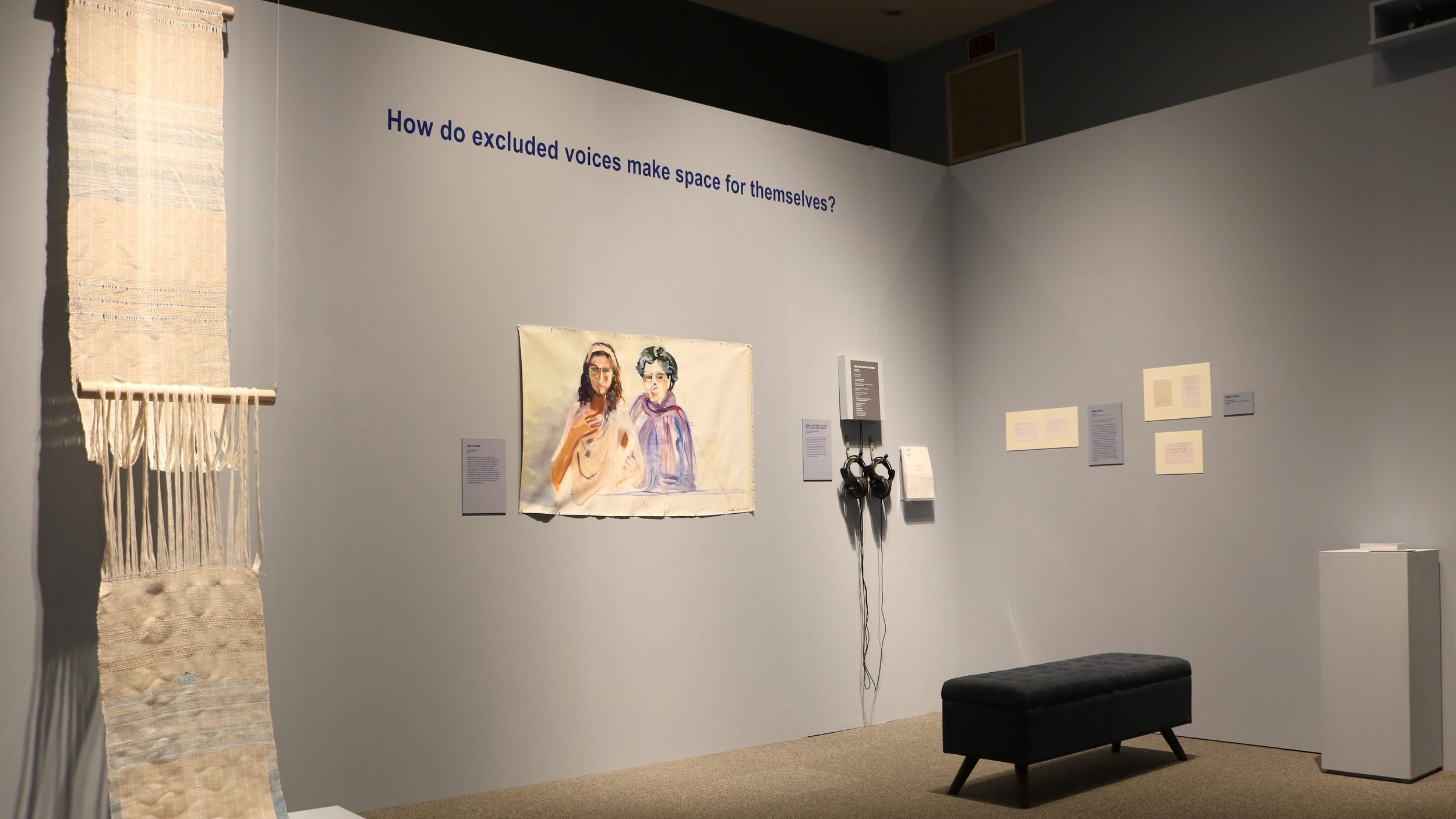

dialogues

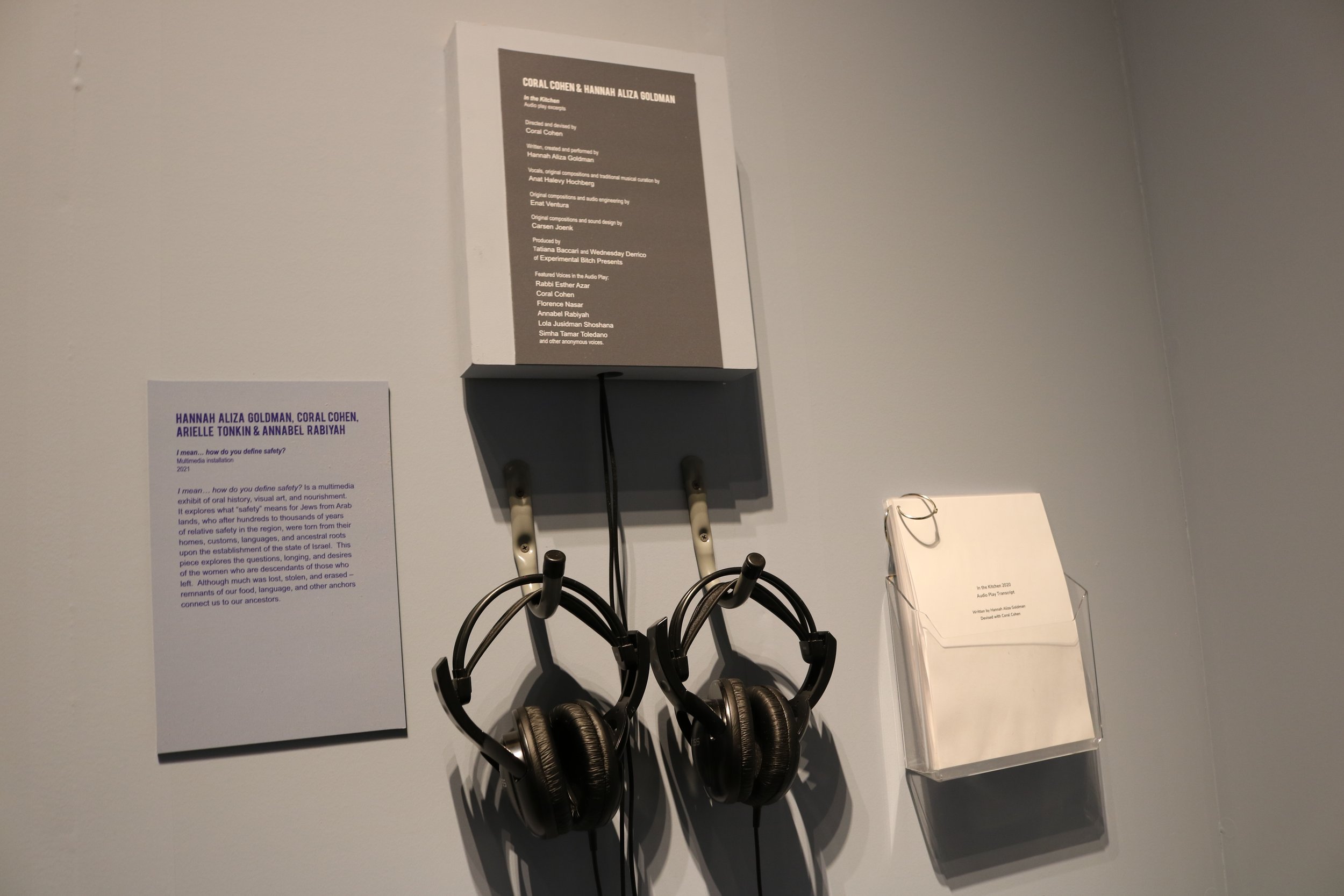

Hannah Aliza Goldman, Coral Cohen, Arielle Tonkin and Annabel Rabiyah

I mean… how do you define safety?

Multimedia installation, 2021

Arielle Tonkin, Hybrid Ritual Object, Salvaged cotton warp (sourced in Chicago) and linen weft (fibers from Kansas and Vilnius, Lithuania, in honor of the Vilna Gaon)", 2016-2017

This impossible hybrid of a tallit (Jewish prayer shawl) and a sajjada (Muslim prayer rug) was an outgrowth of almost two decades of Muslim-Jewish organizing and relational practice. It was woven in 2016-2017 in homage to interfaith protest rituals at Standing Rock and used in performances in interfaith airport chapels around the world to protest the Islamophobic Muslim travel ban.

Curatorial Statement by Liora Ostroff

In Hannah Aliza Goldman’s audio piece Safety, one voice says of their family, “in order to stay safe,” they chose Jewish identity over Arab identity, and in doing so internalized anti-Arab racism and a false binary between their multilayered Arab-Jewish identity. These four artists describe cultural loss and reclamation, investigating the complexity of how trauma, politics, and safety shape cultural expression. Both together and individually through their mixed-media installation, they activate an intergenerational, multi-sensory dialogue about what it means to be safe within a cultural identity that has been politicized, erased, and ruptured by history.

ARTIST STATEMENT BY Hannah Aliza Goldman, Coral Cohen, Arielle Tonkin and Annabel Rabiyah

I mean… how do you define safety? is a multimedia exhibit of oral history, visual art, and nourishment. It explores what “safety” means for Jews from Arab lands, who after hundreds to thousands of years of relative safety in the region, were torn from their homes, customs, languages, and ancestral roots upon the establishment of the state of Israel. This piece explores the questions, longing, and desires of the women who are descendants of those who left. Although much was lost, stolen, and erased – remnants of our food, language, and other anchors connect us to our ancestors.

in the Kitchen (2020)

Directed and devised by Coral Cohen

Written, created and performed by Hannah Aliza Goldman

Vocals, original compositions and traditional musical curation by Anat Halevy Hochberg

Original compositions and audio engineering by Enat Ventura

Original compositions and sound design by Carsen Joenk

Produced by Tatiana Baccari and Wednesday Derrico of Experimental Bitch Presents

Featured Voices in the Audio Play: Rabbi Esther Azar, Coral Cohen, Florence Nasar, Annabel Rabiyah, Lola Jusidman Shoshana, Simha Tamar Toledano, and other anonymous voices.

In the Kitchen was developed and produced by Experimental Bitch Presents (Artistic Director, Tatiana Baccari; Executive Director, Wednesday Derrico) from October, 2019 to December, 2020.

Documentation Of Exhibition, Photograph by Liora Ostroff, 2021

Arielle Tonkin, Becky And Hadar, Oil on canvas, 2016

This painting is part of a series of Feminist portraits of conversations between womxn artists and activists on Ohlone land in the so-called San Francisco Bay Area.

Arielle Tonkin, Transitional Object, Oil on canvas, 2019

Referencing Winnicott’s term used to describe blankets and toys to which young children develop intense attachments, practicing soothing through autoritual and not just parental care, this painting addressed the intergenerational physiological ripple effects of rupture and disconnection from homeland. New surrogate objects, relationships, and rituals can never replace what was lost but that can be used in attachment healing and creating new hybrid culture in diaspora.

ARTIST STATEMENT BY Arielle Tonkin

Arielle Tonkin made two paintings and one woven sculpture, and contributed one amuletic Amazigh vest to be exhibited alongside the radio play In The Kitchen. Just as the play connects Mizrahi personal and collective histories to the culinary arts and cultural traditions of the speakers, these artworks weave Arielle’s mixed Mizrahi lineage and practices. Some of us were raised in the diaspora steeped in our Mizrahi traditions; others of us have fragments. As diasporic artists we are garden-tenders, weavers, painters, and teachers engaging tangible talismans reflecting rituals of recreation and reimagination here in the diaspora towards collective liberation.

Arielle Tonkin, Savta And Her Avatar, Oil on canvas, 2016

Eliane/Aisha Tonkin (neé Lasry) married a U.S. soldier seeking a Jewish host family for Pesach while stationed in Casablanca during WWII. Raising her family in a rural industrial Leomister, MA, Morocco became a fantasy, an abstraction, and Aisha’s descendants are now reconstructing memory through fragments. This image is a trace of a trace of a projection: Arielle created an avatar based on an amalgam of orientalist 18th c. paintings of “Jewesses of the Levant”, revivified according to her own terms. This disappearing reappearing canvas portrait scroll is a cross-generational, multi-temporal, magical, prayerful accompaniment.

Arielle Tonkin, Amuletic Amazigh Vest, Dyed wool, metal sequins

Created by artisans of the Amazigh community and purchased by Rav Kohenet Taya Ma Shere in Ourika (in the High Atlas mountains outside of Marrakech, Morocco), this amuletic woven vest has been used for prayer and protection by Arielle Tonkin as a queer diasporic Moroccan placeholder for a tallit katan. It is one example of how some Arab Jews in the diaspora are reimagining Jewish ritual to connect to parts of our lineage that weren’t transmitted through Jewish institutional life in the U.S.

Annabel Rabiyah

If you are able to cook the food you grew up with, you can recreate home wherever you go.

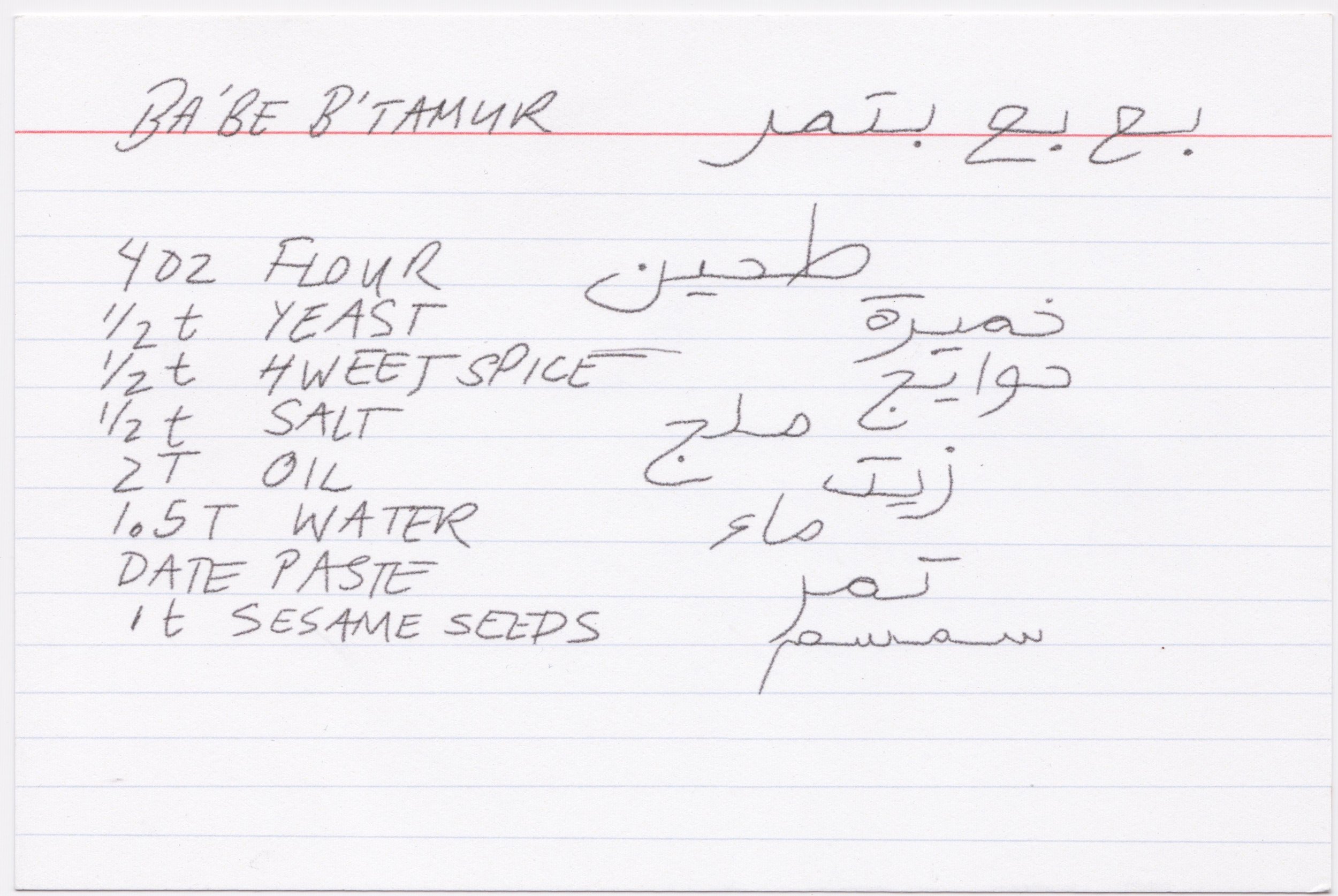

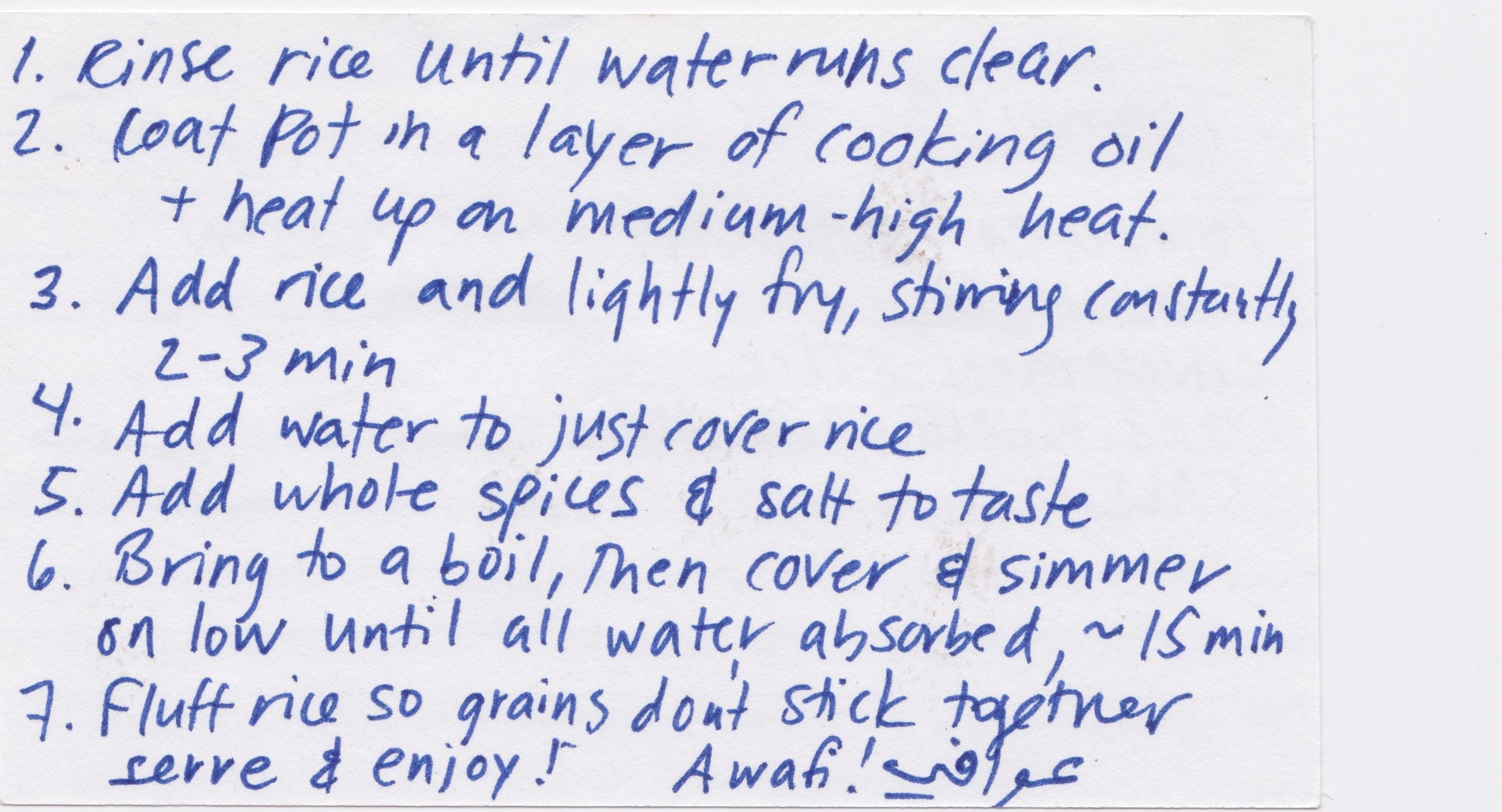

Over the course of just several decades, almost all of Iraq's Jewish community left, and most of them never returned. The Rabiyah family fled the country one night in 1967, without time to say goodbye to friends, and without anything tangible to remind them of home. For many immigrants, especially refugees, recipes are one of the few family heirlooms that remain. Those of us that grew up before the virtual era are familiar with recipes written on index card, illegibly scribbled down with missing instructions or ingredients, in a mix of languages, creased and stained with food. However, most family recipes are passed down by word of mouth. Rabiyah learned the recipe for ba'be, an Iraqi date pastry, in the kitchen by making it with family. The recipe card for ba'be is written in the index card style, as if used for generations. Thinking towards the future, Rabiyah invites you to take a recipe home after the exhibit. The recipe is not one they grew up with, but rather one inspired by their experience preparing Iraqi food, and represents their current experience as an Iraqi in the diaspora.

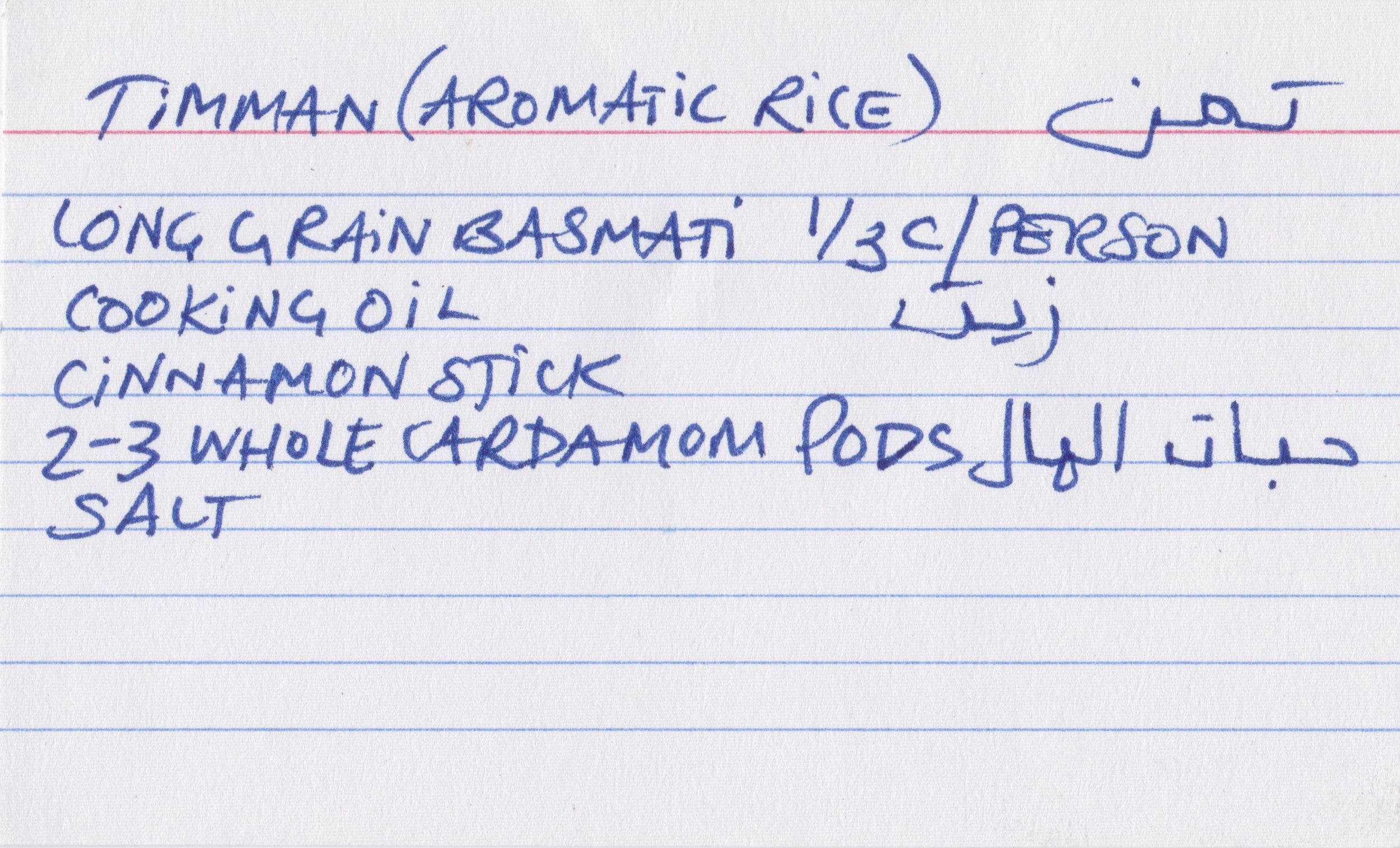

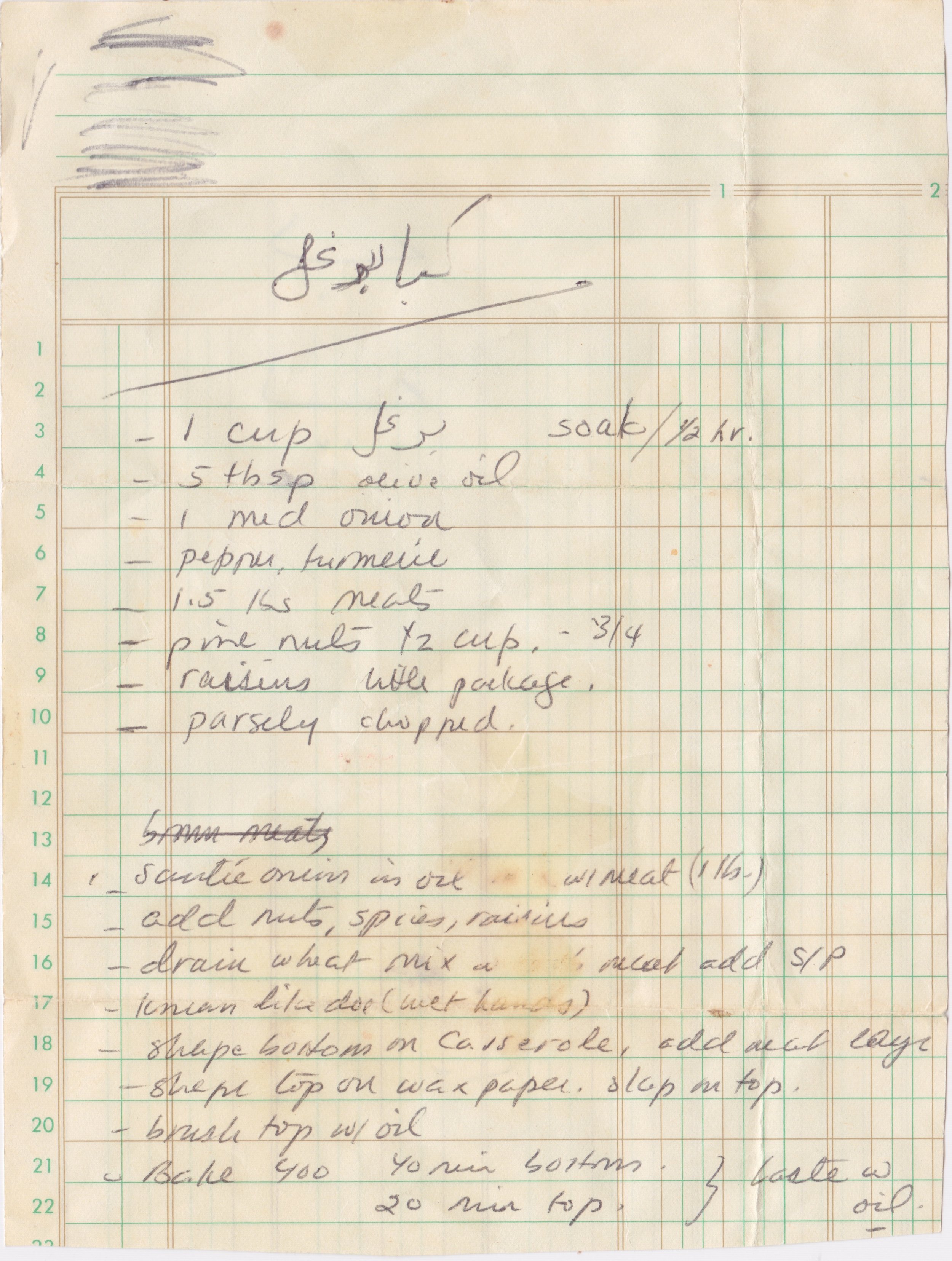

Annabel Rabiyah, Family Heirlooms, family recipes recorded by members of the Rabiyah family, circa 1999

Annabel Rabiyah, Preservation (front), replica of an old family recipe for ba'be, a date pastry, 2020

Annabel Rabiyah, For the Next Generation (back), a simple aromatic rice recipe to be taken home after the exhibit, 2021

Annabel Rabiyah, Preservation (back), replica of an old family recipe for ba'be, a date pastry, 2020

Annabel Rabiyah, For the Next Generation (front), a simple aromatic rice recipe to be taken home after the exhibit, 2021

Annabel Rabiyah, Family Heirlooms, family recipes recorded by members of the Rabiyah family, circa 1999

Annabel Rabiyah, Family Heirlooms, family recipes recorded by members of the Rabiyah family, circa 1999